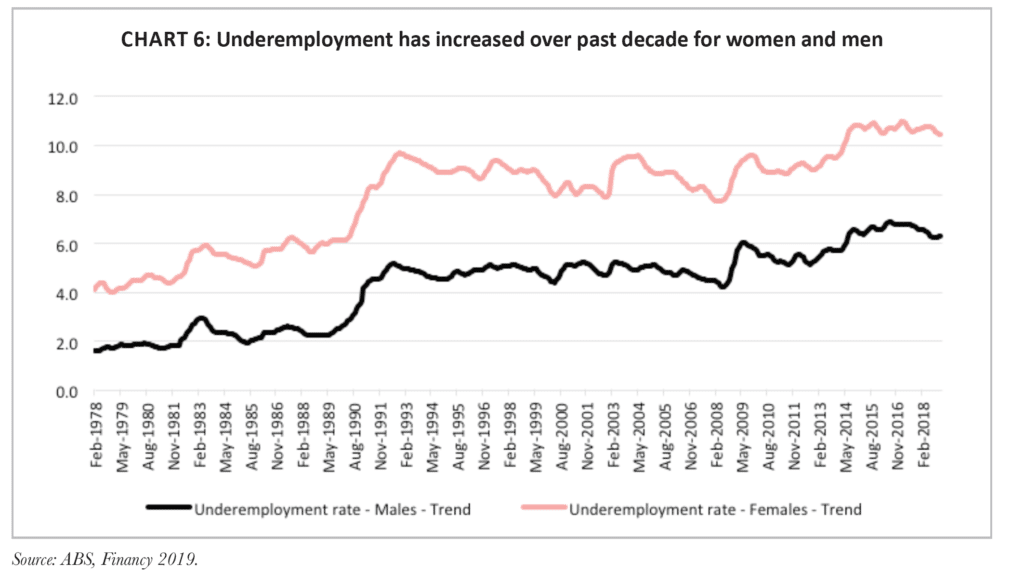

2019 has started with a record number of women in full-time employment and participating in the workforce but when it comes to underemployment we are tens years behind where we should be.

In one of the most significant findings of the Financy Women’s Index for the March quarter, the number of women who identify with being underemployed, which means they generally work part-time, less than 35 hours a week, but are available to and want to work more hours, has actually worsened.

Over the past decade the underemployment rates for both genders have deteriorated, and for women the situation is much worse that it is for men.

In January 2009, the female underemployment rate was 8.8%, which is 1.6 percentage points better than it is today, while for men, the rate was 5.2%, which is a 1.1 percentage point improvement on today.

Let’s look at a chart.

There are likely to be many reasons for this such as there being more women who work part-time as a result of their primary caring roles, which could restrict their ability to find suitable work that fits in with family commitments.

While the level of underemployment has recently come down by 0.2% in January to reflect 10.5% of the total female workforce, compared to 10.7% in January 2018, the lack of change remains concerning.

By contrast the underemployment rate for men aged 15-64 years is much lower and has recently improved at a faster pace. The rate stood at 6.3% in January, down 0.3 percentage points from 6.6% January last year.

There were 650,500 women who identified as being underemployed in January, compared to 651,600 in January 2018.

By comparison, there were 426,200 men underemployed in January, down from 483,800, a year earlier.

In addressing the issue of underemployment, women can certainly take matters into their own hands. Yes they can ask for more hours but there’s no guarantee they’ll get them. For instance, the company they work for may not be able to afford it, or the hours available don’t suit the employee. This is where it’s important to do your research before you put your business case forward for more work, and if that’s not successful, don’t be afraid to try elsewhere.

But an important step for employers is actually asking if their employees are interested in additional opportunities rather than assuming they are not; and consulting with employees to fill roles internally first.

Offering flexible work such as compressed work weeks or working from home arrangements may also enable people to engage in more work, where the traditional 9-5 week may be restrictive.